Fredericton city hall, the justice building and other historic buildings in the city may not be around today if it wasn’t for a passionate architect and the reversal of a city council vote back in the 1970s.

This moment in history is outlined in Vancouver author Adele Weder’s new book Ron Thom, Architect: The Life of a Creative Modernist published by Greystone Books.

The late Ron Thom was a renowned Canadian architect. He’s well-known for his work on Massey College and the Trent University riverside campus.

But Weder said Thom is also known for saving a number of Fredericton’s historic buildings.

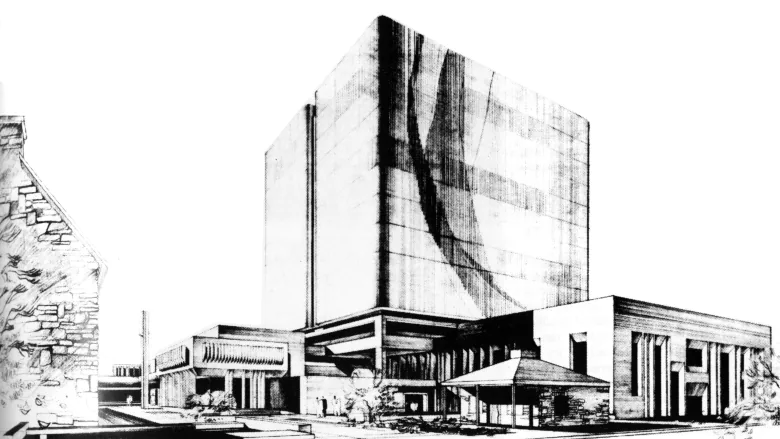

Weder said the city was discussing the possibility of urban renewal and in 1972, a proposal from Marathon Realty was accepted to replace much of downtown’s historic centre with a modernist retail complex. Weder said council backed the proposal with a 6-5 vote.

John Leroux, a trained architect, architectural historian and the manager of collections and exhibitions at the Beaverbrook Art Gallery, said cities were ripping down “enormous” sections of historic downtowns at the time to replace them with large commercial developments.

“Then they realized the error of their ways, but by then it’s usually too late,” said Leroux.

He said this “urban renewal” was going to result in the demolition of City Hall and about “half of the institutional monuments downtown.”

He said it started a heritage movement in Fredericton, which included two people who were central to the movement: Bruno and Molly Bobak.

The Bobaks, two high-profile Fredericton artists, were upset by this decision, said Weder. She said Molly attended the Vancouver Art School with Thom.

By this time Thom was a nationally-recognized architect and the pair called on him to help convince city council to reverse their decision.

“It’s a misnomer that all modern architects just want to destroy history,” said Weder. “Architects like Ron Thom want to preserve and learn and draw from history and have it enrich contemporary architecture, so he loved historic Fredericton.”

Weder said she came to Fredericton in 2011 and spoke to the Bobaks. She said they recalled Thom’s plea to council as a “fiery speech.”

She said Thom worked with local historians from Heritage Trust to build local opposition.

“He lent it an external authority, a moral force, because he was nationally-renowned,” said Weder. “He came in with this moral authority of being a contemporary architect and saying, ‘This is wrong, you must not destroy your past.'”

Weder said city council did reverse the decision narrowly, 6-5 on a technicality.

‘A very different place’

Leroux said the same company that wanted to build a development in place of Fredericton’s historic downtown ended up building Kings Place a block away.

“Picture Kings Place, you know, but twice as big replacing a lot of the beautiful historic buildings downtown,” said Leroux. “And that’s what downtown Fredericton would be.”

Leroux said he thinks Fredericton would be a very different place if the development had gone ahead.

“I think you would have a real dead zone in the middle of downtown… It’s civic identity is based upon the idea that we have these heritage streetscapes and neighbourhoods,” said Leroux.

“Phoenix Square, it’s where people gather, it’s where they go to celebrate and support and protest and gather and so that would be gone. Because no one does that now in front of Kings Place.”

With files from Information Morning Fredericton

This story was originally published in CBC News on Oct. 10, 2022.